As a consulting winemaker, I have made the general observation that winemakers tend to take a lot of time in selecting yeast strains to ferment grapes. Many spend significant time deciding if the marketing terms related to wine descriptors they expect to arise by the end of primary fermentation are what they desire in their wines. In some cases, a winemaker may mull over these decisions over the course of weeks.

Then when I ask about yeast nutrition considerations, two immediate themes pop up in response to my inquiry:

- We’ll just use what we have.

- We typically apply the same nutrient and nutrient concentration to each fermentation.

Sound familiar?

Here’s the bottom line: if you’re treating your yeast nutrition without the scrutiny often given to yeast strains, then you’re not optimizing the qualities produced by that yeast strain. In fact, it’s a flip of the coin in terms of whether the wine will actually reflect all that you saw marketed to you.

The yeast’s performance characteristics and resulting wine quality depend on other production practices, including the yeast nutritional strategy. In fact, if the yeast receives inadequate nutrition (too little or too much), the result is usually a wine that suffers from hydrogen sulfide. At that point, the winemaker has lost the option of benefiting from the aromatic development that the yeast produces. This is especially true in thiol-rich wine grape varieties in which later copper sulfate additions will end up dulling the overall wine aroma and flavor.

Why Winemakers Avoid Yeast Nutrition Changes

I observe winemakers avoiding yeast nutrition strategies for two primary reasons:

- They rely on information they were taught previously and do not stay current with updates to yeast nutrition. Keep in mind that subtle updates are made annually.

- It’s a challenge for many wineries that aren’t located on the West Coast to easily measure yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN). This practice requires some time, planning, and a financial allocation to make it work effectively.

Let’s address these two observations individually.

But First, a Reminder: Winemakers Cannot Predict YAN

I have been giving public speaking engagements about yeast nutrition since the mid-2000’s. That’s a little over a decade of talking about YAN. One may think not a lot really changes during that period, but in fact, yeast nutrition guidance changes slightly each year.

Here’s the one thing that hasn’t changed: there is no way for the winemaker to predict the YAN concentration of the must at the start of fermentation.

To date, there is no way a grower can control YAN in a grape variety. When I worked with two research plots that grew 30 different wine grape varieties within one acre of space, we saw YANs range from low to average to very, very high. That was over one acre of land.

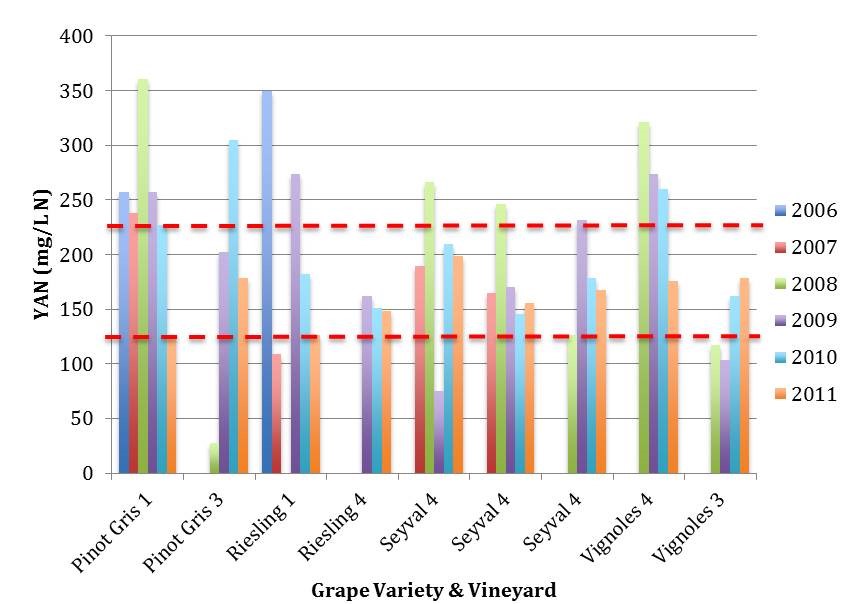

Additionally, in 2012, I analyzed nitrogen data collected by a regional winery that had been recording yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN) data they collected for over 6 years. The data was unique in that it tracked YAN concentrations from single varieties planted in single vineyard blocks over a large stretch of time. Not surprisingly, the data confirmed variation in nitrogen concentrations prior to fermentation on an annual basis (Figure 1).

Remember: the only current consistency about yeast nutrition is that we can’t predict it. It has to be measured and it has to be considered each vintage year, both financially and production-wise.

That’s why I often spend so much time discussing yeast nutrition strategies with winemakers.

Yeast Nutrition: An Ever-Changing Winemaking Practice

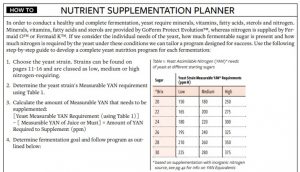

If you read the 2020 supplier handbooks, you may see that recommendations for yeast nutrition adjustments have changed (Figure 2). For example, starting Brix and yeast strain nutritional needs are now better defined to emphasize how much YAN is optimal for that fermentation. This is clearly illustrated in the Scott Lab’s handbook instructions, pictured.

Gone are the days of just getting to 150 mg N/L of YAN; now, winemakers need to be aware of what optimal concentration of nitrogen is required for their yeast strain under specific fruit chemistry conditions.

What does this mean for the winemaker?

Winemakers need to make time annually to review their nutrient supplier’s recommendations. Since this is an area of winemaking that routinely changes, the winemaker has to remind himself/herself to review their own practices. This general review and planning stage is covered in the DG Winemaking Pre-Harvest Prep Timeline. It acts as a reminder for winemakers to review essential processes in the cellar in order to optimize harvest season.

It also means winemakers have to understand how to add up YAN from both analytical assessment and winemaker supplementation during primary fermentation. If you struggle with this concept, you can download the free YAN Calculations Worksheet to practice converting nutrient dosage rates into nitrogen concentrations that contribute to YAN.

Measuring YAN is a Challenge

The fact that YAN is variable means that winemakers need to understand why measuring YAN and treating fermentations specifically to the known YAN concentration is so important. This is the only way winemakers will make time measure YAN in addition to the usual lineup of juice analyses (Brix, pH, and TA).

If you find yourself at a loss as to what YAN is, why it is important, and how it contributes to wine quality, the webinar, “YAN Part 1: What is YAN?” is a perfect review for you! This webinar goes over the fundamentals associated with yeast nutrition and integrates how YAN can be used to align with wine style expectations.

However, the second challenge associated with YAN is getting the fruit measured to determine YAN prior to the start of fermentation.

Many winemakers make guesses with YAN because measuring YAN is time consuming and can be costly. The equipment I generally recommend for measuring YAN can run wineries an initial investment upwards of $2,000.

The other option for wineries is to send out juice samples to a wine lab. For wineries in close proximity to a wine lab, this is not a huge inconvenience. But for many wineries across the continental U.S., this involves:

- prepping a juice sample,

- packaging a juice sample,

- getting the sample shipped, and

- then waiting for the YAN result.

Again, this sounds like a difficult task.

But by breaking it down into these steps, a winemaker can actually plan, both logistically and financially, to get YAN results annually. Luckily, DGWinemaking covers how to plan for this and make it work for the winery so that it becomes habitual and easy. This is extensively outlined in the webinar, “YAN, Part 2: Measuring YAN.”

Finally, I review the risks associated with various YAN ranges in a given must/juice and the options winemakers can use to treat the fermentation in the final YAN webinar, “YAN, Part 3: Adjusting YAN during Fermentation.”

If you find yourself faced with stuck/sluggish fermentations or a fair amount of fermentations that result in hydrogen sulfide development, then these lessons are directed for you. YAN, Part 3 is the most advanced of the three webinars, going beyond fundamentals to spur new ideas for winemakers that want to enhance their yeast and yeast nutrition strategies.

These webinars come with downloadable notes that can be used immediately.