Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Volatile acidity (commonly abbreviated as “VA”) is the concentration of accumulated volatile acids, or those acids that can be separated through distillation. In wine, acetic acid is the primary volatile acid. Acetic acid is also the primary acid associated with vinegar. This is why high VA is associated with the detection and potential perception of “vinegar” in wine.

However, as I have noted before, many winemakers incorrectly assume they can detect the presence of acetic acid before it completely spoils the wine.

White wine can contain up to 1.20 g/L acetic acid while red wine can contain up to 1.40 g/L acetic acid per the guidelines from the CFR. However, these values are well under the concentration of acetic acid commonly found in commercial vinegar, which is about 4-8% (roughly 40 – 80 g/L of acetic acid). Thus, by the time the wine smells like that of commercial vinegar, it’s sincerely passed the allowable limit in wine.

Furthermore, most individuals cannot sense acetic acid until it reaches 1.60-1.70 g/L, which, if you are reading this post carefully, is also past the allowable limit for wines.

Thus, many high VAs go undetected by winemaking operations that choose not to analytically monitor the VA through production.

The Impact of Elevated VA Wines

One of the reasons why I talk about VA so much is because it’s one of the most frequently found wine faults I find in commercial table wines both as a consultant and as a wine consumer.

I recently purchased a $25 – $35 Pinot Noir from Oregon. The Pinot was from a wine brand that I bought regularly as it’s considered a “value” Pinot and distributed nationally. Unfortunately, I found the current vintage had so much VA in it that I found it undrinkable, lacking any varietal character usually associated with the wine. I was highly disappointed in this wine given the price point and the strong quality deviation from previous vintages.

While I am only one wine consumer of a largely distributed wine, I think it’s important to note that I used to be a routine purchaser of this wine. However, given that I now found it undrinkable, it’s likely I will not only avoid this current vintage for the duration it is on retail shelves, but I may also be hard pressed to purchase this wine in the future.

In other words, the brand just lost a regular, repeat customer. Without being able to rely on the quality, I’d rather spend the $25 – $35 elsewhere.

Again, I’m one individual, but I imagine there are other customers out there like me that may notice sensory changes in their go-to wines. Thus, over time, such dips in quality can have notable influences on the sale of wines, especially in today’s competitive markets when something of better quality is easily attainable.

How Can a Winery Monitor VA?

While many people may not be able to recognize acetic acid accumulation until it hits the 1.60 g/L threshold, elevated levels of acetic acid can start to impact the overall sensory of wines around 0.70 g/L of acetic acid. The overall influence of the elevated acetic acid concentration will vary from wine to wine, but I do find this to be the point at which many wines are sensorially altered due to the acetic acid concentration.

Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Once a wine hits 0.7 g/L acetic acid, I consider the VA “elevated.” In this case, an elevated VA refers to an acetic acid concentration that is high enough to influence the wine’s sensory characters and quality, but low enough to fall under legal limits. The easiest way to minimize the sale of elevated or high VA wines is through routine monitoring practices.

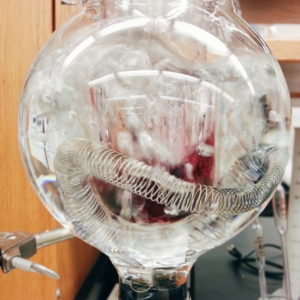

Most wineries monitor VA through the use of a cash still, a rather intimidating piece of wine analytical equipment that is somewhat simple to operate. While using the cash still, and subsequent titrations, can be time consuming, individuals that routinely use the apparatus can become quite proficient and efficient on it.

In reality, VA is one of those analytes that can get monitored at specific time points during the wine’s production such as post-primary or post-MLF. The benefit to having routine time points for measuring VA is that the winemaker can start to identify gaps in production standards by noticing trends in results. Additionally, it’s more probable that a problem wine will get found before the problem becomes time consuming, expensive, or both to remediate. For example, wineries without the use of tank temperature control are better able to develop necessary timelines for bottling given they can identify increases in VA as the wine’s temperatures start to warm.

I’m still a proponent of measuring VA after primary fermentation, even if the wine is set to go through malolactic fermentation (MLF), to determine the wine’s starting VA. This allows winemakers to then compare the change in VA after additional wine processes such as MLF and through storage. DGW Clients and Members may use the Production Guide: Wine Analysis Expected Results, which details what numbers I associate with good VA levels at the end of MLF and through wine storage, especially with wines in barrels.

Remediating Wines with VA: The Challenges

Monitoring is also important to avoid remediation of high VA wines.

Unfortunately, the “best” way to remediate high VA wines is the use of reverse osmosis (RO) technology to reduce (not eliminate) the VA of that wine. However, access to RO technology remains scarce or expensive for many wineries throughout US winemaking regions.

Thus, many wineries are reliant on blending strategies to mitigate the effects of VA on the wine’s quality. While blending can help reduce the VA of a finished wine, it provides opportunities for many other problems to occur:

- Determining where a lower quality wine can get allocated without ruining the reputation of the brand in the finished blend.

- Pre-treating the spoiled wine to reduce microbial populations (which is expensive and time consuming) in order to minimize the risk of spoiling a larger volume of wine when blended.

- Potentially losing out on one of the winery’s portfolio items due to the incidence of high VA in that wine.

Thus, it is almost always more beneficial to avoid high VA issues, as opposed to remediating them. Again, the most obvious way to try to do this is through routine analytical monitoring practices.

How Can You Get Better at Monitoring VA?

Many winery operations can improve VA monitoring practices either by

- starting to measure VA,

- creating more thoughtful time points for routine monitoring of VA, or

- improving their VA analytical techniques.

If you are a part of the DGW Community through Membership or as a Client, there are several tools that can help you improve your needs for your winery:

- Improve Your Analytical Prowess: Use the Volatile Acidity (VA) Protocol for instructions on using the cash still and subsequent titrations to accurately measure VA. If you need more help, refer to the Winemaking Lesson: Using the Cash Still for Volatile Acidity Analysis. This lesson provides more detail with photos and video on how to use the cash still and calculate VA for a wine.

- Start Measuring VA: If you haven’t previously measured VA for your wines, now is a great time to start. Use the Production Guide: Juice/Wine Analysis Recommendations as a guide for the minimal time points in production in which you should be measuring VA.

- Go Beyond Routine VA Monitoring Practices: If you are already monitoring VA according to the bare minimum recommendation, above (Production Guide: Juice/Wine Analysis Recommendations), then you are on a good track. If the winery frequently experiences VA challenges, check out where gaps in production may be by reviewing VA results for your wines. It’s possible you may find a place in production that regularly increases the VA. For example, barrel management while wines are in barrel can be a challenge for many winery operations. Using the Barrel Management: Best Practices Production Guide may be helpful in identifying if the winery is properly managing the barrel program to minimize the incidence of wine spoilage.

If you aren’t a part of the DGW Community, with access to all of the materials mentioned above, you can find out more about our Memberships and Client Services, here.

Remember, every wine is going to have some VA. But keeping the VA in check is all up to the winemaker!

The views and opinions expressed through dgwinemaking.com are intended for general informational purposes only. Denise Gardner Winemaking does not assume any responsibility or liability for those winery, cidery, or alcohol-producing operations that choose to use any of the information seen here or within dgwinemaking.com.