Malolactic fermentation (MLF) is a common deacidification technique used to biologically convert malic acid retained in grapes and wine to lactic acid and carbon dioxide (Krieger 2005). MLF is conducted through proliferation of native lactic acid bacteria (LAB) or by inoculation of commercial LAB strains. The three existing genera of LAB in wine are Lactobacillus, Oenococcus, and Pediococcus (Krieger 2005, Iland et al. 2007), or by inoculation of commercial LAB strains.

Commercial strains, Oenococcus oeni, are often preferred as this strain of LAB best conducts MLF (Waterhouse et al. 2016). O. oeni is relatively predictable in its ability to convert malic to lactic acid, and several commercial strains have various capabilities of producing the aromatic byproduct, diacetyl. Diacetyl provides a buttery flavor or aroma that is desired in some styles of wine, such as oak-aged or reserve Chardonnay.

Monitoring MLF at the Winery

LAB can be inoculated at several stages of wine production:

- Before primary fermentation,

- During primary fermentation,

- Near the end of primary fermentation,

- After primary fermentation is complete (Iland et al. 2007).

Each stage in which LAB can be added to the wine will offer a number of advantages and disadvantages to the winemaker. Ultimately, when LAB inoculation occurs can affect wine quality.

Once MLF progresses, it’s off to the races.

Many wineries find it affordable and convenient to monitor MLF progression through paper chromatography. Enartis USA, and Presque Isle Wine Cellars are example suppliers that offer decent kits and parts for paper chromatography. Many other home winemaking supply stores offer kits and instructions. For a look at free protocols, you can check out Enartis USA’s or Midwest Supplies.

Paper chromatography is simple and convenient, but it does come with its limitations.

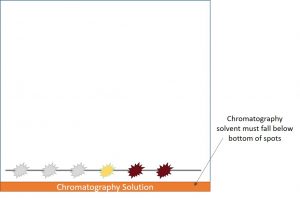

In the paper chromatography process a set of acid standards (tartaric, lactic, and malic) and a series of wine samples are all spotted onto a piece of chromatography paper across a penciled straight line (Image 1).

After the dots receive sufficient time to dry, the paper is rolled up into the shape of a tube, and the ends are secured with a stapler. Note that the paper edges should not overlap during the stapling process. Afterwards, the tube of paper is placed into the chromatography solvent. The chromatography solvent, a bright orange color, should not reach the bottom edge of any of the acid or wine spots (Image 2).

If the solvent hits the bottom edge of the spots, your chromatography paper will appear “blank” when it dries.

The paper can be emerged in the solvent for about 4 hours or overnight. As the solvent moves up the paper, so will the dots. If you are testing red wine samples, you’ll see some of the color pigments separate during this process. After the solvent has reached the top edge of the paper, it is removed from the solvent and allowed to dry. The solvent is hazardous, so proper lab safety care should be taken while the paper chromatogram dries.

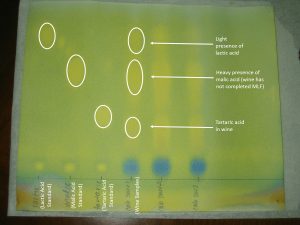

When it dries, the paper should turn a blue or blue-green and show a series of yellow spots that are related back to the acids. Image 3 shows a good example of a finished chromatogram.

In theory, when all of the malic acid is converted to lactic acid during MLF, the malic acid dot for a wine will “disappear” while the lactic acid dot will appear brighter. However, as many people may note, it is not unusual to find a very faint dot of malic acid remaining even though MLF has been completed. How is that possible?

Testing for Residual Malic Acid

However, to ensure that your MLF is completed, it is best to use enzymatic analysis to determine the concentration of malic acid and lactic acid in your wine. Wines with less than 0.3 g/L of malic acid are typically considered “dry” and that MLF is complete. Some winemakers may want to deplete the malic acid concentration below this limit.

Wineries with access to a spectrophotometer, proper pipettes, and an enzymatic kit can run this analysis at the winery. Without this equipment, wines should be submitted to an ISO accredited wine lab.

What to do if things go wrong?

Nonetheless, even when using commercial strains of LAB, MLF can offer several challenges to winemakers. MLF is not always easy to complete efficiently. Several factors can contribute to a sluggish or stuck MLF including:

- Inhibition by sulfur dioxide, alcohol, temperature or oxygen.

- Inadequate nutrition.

- Competition from other microorganisms (e.g., acetic acid bacteria, native LAB).

- Presence of copper ions or residual pesticides (Iland et al. 2007).

A stuck MLF can be a difficult winemaking situation. Wines are usually left unprotected with very little sulfur dioxide in the wine. Additionally, wines are usually maintained within the ideal LAB growing temperature, around 68°F. However, this warmer temperature is also ideal for a number of potential spoilage microorganisms to grow. Warm temperatures and a lack of adequate antimicrobial protection offer ideal conditions for growth of spoilage microorganisms.

Developing Best Practices for MLF

Now is the time when winemakers acknowledge that MLF may be stuck. While many winemakers may quickly reach to re-inoculate a tank or barrel with MLB, I’d recommend avoiding this strategy as a first step. Many of the suppliers have indicated that over-inoculation of MLB strains can actually lead to more problems in your wine without actually solving your problem or re-starting a stuck MLF. (This is important advice, as the suppliers make more money off of new MLB purchases.)

In February, we’re going to review best practices associated with the MLF process through the Darn Good Winemakers session on Monday, February 18, 2019 at 12:30 PM (EST). This webinar, “The Dot Races: Best Ways to Know MLF is Complete” will cover:

- A more detailed review of paper chromatography

- A discussion on enzymatic analysis

- Monitoring MLF procedures

- Re-starting a stuck MLF

You can register any time to become a Darn Good Winemaker. Your membership comes with 12 consecutive monthly webinar and coaching sessions. Topics are decided by the Darn Good Winemaker community, and our Q&A sessions after the webinar are time for you to ask any questions pertaining to the wine you make without ever paying a consulting fee.

All sessions are recorded and can be viewed by current DGW clients and Darn Good Winemakers at any time.

DGW clients can also access the Cellar Tool Production Guide: Re-Starting a Stuck MLF by logging into the DG Winemaking website. This DGW Production Guide provides 5 different steps the winemaker can take to re-initiate their stuck MLFs.

References

Iland, P., P. Grbin, M. Grinbergs, L. Schmidtke, and A. Soden. 2007. Microbiological Analysis of Grapes and Wine: Techniques and Concepts. Patrick Iland Wine Promotions Pty. Ltd. Australia. ISBN: 978-0-9581605-3-7

Krieger, S. 2005. The history of malolactic bacteria in wine. In Malolactic Fermentation in Wine: Understanding the Science and the Practice. Lallemand, Inc. Montreal, Canada. ISBN: 0-9739147-0-X

Waterhouse, A.L., G.L. Sacks, and D.W. Jeffery. 2016. Understanding Wine Chemistry. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. United Kingdom. ISBN: 978-1-118-62780-8