As many in the wine industry transition from packaging wine in traditional 750-mL bottles to trying out alternative packages like cans, pouches, and Tetra packs, new stability problems emerge. It’s easy to assume that the package has no real impact on the wine other than potential quality characteristics (e.g., aromatic intensity, aromatic profiles, shelf-life or longevity), but, in fact, the package also plays a part in potential microbial spoilage that can survive post-packaging.

Aerobic vs. Anaerobic Microorganisms

The terms “aerobic” and “anaerobic” describe the environmental air conditions that may influence microbial growth.

- Aerobic describes the need for oxygen to survive. Wine microorganisms that require oxygen for their growth and reproduction include acetic acid bacteria or Saccharomyces yeast.

- Anaerobic indicates that the microorganism does not require oxygen for growth. In fact, the presence of oxygen may inhibit growth of that microorganism.

Microorganisms may also exhibit growing conditions in both the presence and lack of oxygen. An example of one of these organisms is most species of lactic acid bacteria, including Oenococcos oeni. Most of the lactic acid bacteria in wine are considered “facultative anaerobes,” meaning while they can grow in the presence of oxygen, they thrive in conditions in which oxygen is not available. Yeasts that can grow in anaerobic conditions include Brettanomyces and Zygosaccharomyces.

What does this mean for the wine?

With a new package, especially a package like cans in which an anaerobic environment is created, the winemaker should consider the potential spoilage microorganisms that could thrive in the wine post-packaging. While the presence of common Saccharomyces inhibitors like carbon dioxide, potassium sorbate, and sulfur dioxide may work for wine packaged in glass bottles, their use in alternative packages may not be as effective in anaerobic packages. Some strains of Zygosaccharomyces, for example, can grow in anaerobic environments with sulfur dioxide levels over a 0.85 ppm (molecular) free sulfur dioxide and with a 200 ppm sorbic acid addition.

How to Minimize Problems with the Integration of New Wine Packages

Switching from traditional glass bottles to alternative packages changes the game in terms of what can spoil the wine. However, it doesn’t change the need to take proactive steps to minimize the risk of post-packaging problems.

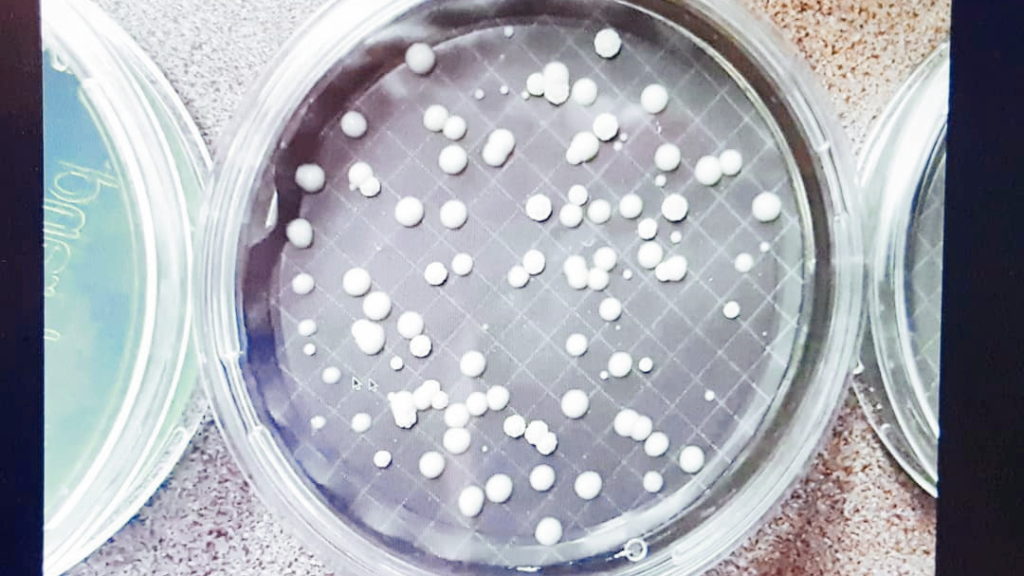

1. Know What to Measure

With traditional wine bottles, winemakers can rely on free sulfur dioxide concentrations, and potentially a standard addition of potassium sorbate, to minimize their worries of post-bottling fermentation. (If you want to review some of these concepts, check out our Stop the Pop! webinar available to Darn Good Winemakers members and DGW clients.) With alternative packages, depending on how the wine was made (i.e., fermented from fresh grapes versus fermented from a wine concentrate), the winemaker may want to consider pre-packaging microbial testing (e.g., plate counts, PCR) to scan the wine for microorganisms that can survive in anaerobic conditions. Since some anaerobic microorganisms are more resistant to common wine preservatives, knowing a potential threat can help the winemaker take extra precautions to remove the risk or consider bottling the wine instead of using an alternative package.

2. Sanitation, Sanitation, Sanitation

Sanitation is going to be the winemaker’s best line of control against post-packaging issues. If the winery does not have good sanitation practices in place, then the likelihood of picking up contaminating spoilage microorganisms increases, especially during bottling operations. Having sterile filtration is not enough to ensure the wine is 100%-microorganism free when it goes in the package. If you struggle with good sanitation practices, jump into our Winery Sanitation Steps that Work! webinar (a part of the Darn Good Winemakers membership program!) that provides a list of steps on how to properly clean and sanitize winemaking equipment.

3. Also, Good Cleaning Practices

Without good physical cleaning practices, a sanitizer application can be useless, and the winemaker could be throwing money down the drain. Most winery equipment needs a good thorough cleaning before sanitizer can be applied to it. If debris or dust is seen on equipment, then it cannot be sanitized properly. Furthermore, if the equipment is sticky or has spots of “goo” on it, then it cannot be sanitized properly.

Most of the alternative packaging issues I have seen occur as a result of poor cleaning and sanitation practices that are appropriate for that packaging line. Furthermore, the perfect storm for post-packaging issues stems from a lack of quality assurance (QA) checks on the packaging line to ensure it is working properly, properly sanitized, and that the wine meets specifications for packaging. These check points are used for each packaging run to provide documented reassurance that the line and product is within appropriate specifications to minimize post-packaging risks. Without these check points, the operator and winemaker never know if an issue has risen that could put the product at risk. When placed in storage environments that may stress the product, it is only a matter of time before spoilage issues occur.

Managing bottling QA is intense, but it isn’t impossible for operations of any size to incorporate better practices. Does your operation need help with improving the bottling or packaging success rate? Access our three-webinar series course, Everything You Wanted to Know about Wine Bottling, for practical advice on how to ensure bottling or packaging with alternative wine packages is successful with minimal post-packaging issues.