Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Malolactic fermentation, or MLF, a deacidification process in which malic acid is biologically converted to lactic acid and carbon dioxide (Krieger 2005). The process is “biological” because it is carried out by living lactic acid bacteria (LAB): Lactobacillus, Oenococcus, and Pediococcus (Krieger 2005, Iland et al. 2007) that are native to the grapes or through inoculation of commercial LAB strains.

Like other microorganisms, LAB have ideal temperature ranges for growth and metabolism. As many wineries approach colder daily temperatures, it’s important to monitor environmental and storage conditions of those wines that are undergoing MLF until the process has completed. Otherwise, MLF can become stuck or “pause” until temperatures warm again. If the winemaker is not properly monitoring MLF, a stuck MLF may lead the winemaker to believe MLF has completed.

In a previous Darn Good Winemakers webinar, “The Dot Races,” we addressed practical MLF monitoring techniques. We also discussed limitations of paper chromatography or not monitoring MLF at all.

Case Studies: When MLF Causes Gas in Bottles

One common theme I’ve found regarding MLF is its tendency to re-start post-bottling. Several wineries have approached me when they believe bottled wine is re-fermenting due to a yeast fermentation, when in fact, we discover that it is actually MLF completing in the bottle. “How can this happen?” they wonder. The wine had both added potassium metabisulfite and potassium sorbate at bottling. Many also go through a sterile filtration process at bottling.

But there are several realities to this common problem associated with MLF re-starting in a bottle that winemakers may be unaware of:

- Often, winemakers having not confirmed MLF completion through enzymatic analysis to ensure the malic acid concentration is considered “dry.”

- The free sulfur dioxide concentration post-bottling has usually dropped so low that it is not providing adequate antimicrobial protection. Refer to the Darn Good Winemakers webinar, “Demystifying Sulfur Dioxide” for a better understanding on how sulfur dioxide works in wine.

- Winemakers incorrectly believe potassium sorbate will inhibit all microorganisms in wine. In fact, potassium sorbate is only inhibitive to certain strains of yeast and mold when used at proper dosage rates. Furthermore, as potassium sorbate breaks down, its antimicrobial nature becomes inactive.

- Many wineries fail to ensure their sterile filtration process is working properly with filter integrity testing, such as the bubble point test. You can find a protocol and video on proper bubble point testing methods provided by Scott Labs.

- The assumption that the wine is sterile as it goes through bottling simply because the wine was passed through a sterile filter is false. Once the wine re-touches any winery equipment (i.e., hoses, the bottling line, bottles, etc., the wine is no longer sterile. This is why bottling line sanitation and quality assurance during bottling (or packaging) is so important. For good winery cleaning and sanitation concepts that any winery can conduct, please watch the Darn Good Winemakers webinar, “Winery Sanitation Steps that Work!”

Furthermore, with the integration of unique wine packaging, such as cans, many winemakers are surprised to find that the packaging environment may be more conducive for LAB growth. LAB are considered facultative anaerobic microorganisms. This means that while LAB can survive and grow with oxygen exposure, most prefer a lack of oxygen. Therefore, packages like cans provide the perfect anaerobic conditions for LAB growth. Coupled with warm distribution, storage, and retail temperatures, these packages create an ideal situation for LAB.

What can Wineries do to Control MLF?

First, wineries should ensure a MLF is actually completed before making sulfur dioxide additions to the wine. Do not assume that paper chromatography or the lack of hearing or seeing gas produced through MLF is an indication MLF is all finished. To do this, wineries should measure residual malic acid and ensure the wine is “dry.”

If the wine is not “dry” for malic acid, but the MLF is not progressing, then a winemaker should work on re-starting the MLF to complete it sooner rather than later. Without adequate sulfur dioxide levels to preserve the wine, waiting until the warmer Spring or Summer months may not be advantageous for the winemaker. Often, this waiting period leads to wine spoilage usually by rising levels of volatile acidity due to acetic acid bacteria activity.

Re-starting a stuck MLF can be a tricky and time-consuming process. Unlike primary fermentation, constantly adding commercial LAB can actually be more problematic than helpful. Thus, for the November Darn Good Winemakers webinar, we are going to discuss best practices for managing a MLF and re-starting it when necessary.

In addition to access during the “Re-Starting a Stuck MLF” webinar, your Darn Good Winemakers annual membership provides you with:

- a year’s worth of monthly webinars,

- exclusive downloadable content specific to each webinar,

- continued access to recorded Darn Good Winemakers webinars,

- monthly Winemaking Advice Hours where you can ask all of your winemaking questions without paying a consulting fee,

- exclusive bi-monthly e-blasts,

- locked-in rate for consecutive years of membership, and

- annual renewal options for membership.

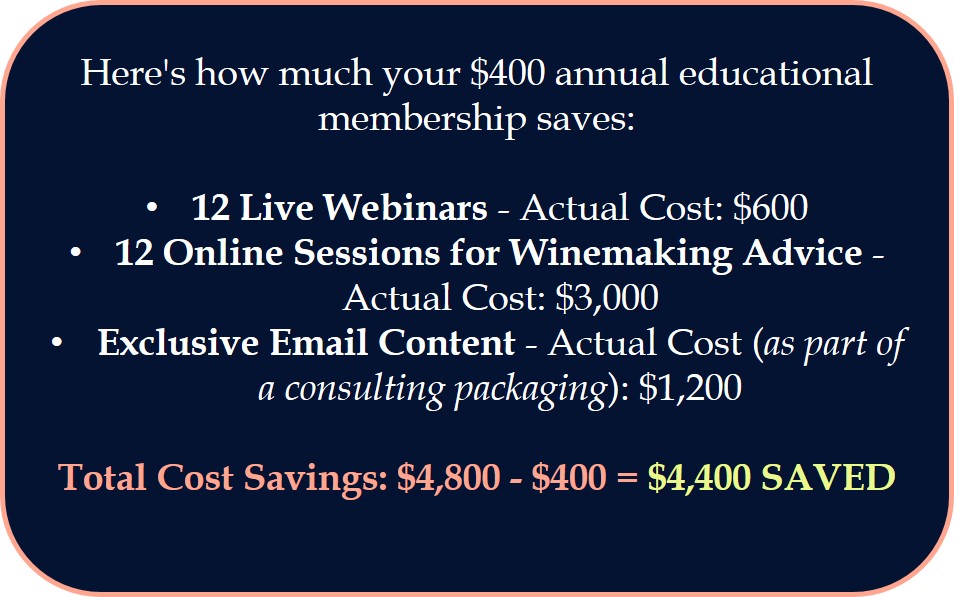

Need a resource to ask some winemaking questions once and awhile, but can’t afford the consulting fee? Here is what your Darn Good Winemakers membership saves you:

References

Iland, P., P. Grbin, M. Grinbergs, L. Schmidtke, and A. Soden. 2007. Microbiological Analysis of Grapes and Wine: Techniques and Concepts. Patrick Iland Wine Promotions Pty. Ltd. Australia. ISBN: 978-0-9581605-3-7

Krieger, S. 2005. The history of malolactic bacteria in wine. In Malolactic Fermentation in Wine: Understanding the Science and the Practice. Lallemand, Inc. Montreal, Canada. ISBN: 0-9739147-0-X