Did you know?

All of the resources listed in today’s post on malolactic fermentation (MLF) are now available to individuals that become a DGW Insider. DGW Insiders receive exclusive access to almost all of the content available on dgwinemaking.com: Articles, Cellar Tools, Webinars, and more!

Click here to learn more about becoming a DGW Insider with a monthly membership or annual price discounts.

Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Malolactic Fermentation (MLF)

Malolactic fermentation is a deacidification process in which malic acid is biologically converted to lactic acid and carbon dioxide (Krieger 2005). The process is considered “biological” as it is carried out by living lactic acid bacteria (LAB): Lactobacillus, Oenococcus, and Pediococcus (Krieger 2005, Iland et al. 2007) that are native to the grapes. Though, many winemakers opt to inoculate for MLF with use of commercial LAB strains.

LAB selection is actually a fairly important consideration as LAB have ideal temperature ranges and growing conditions for growth and metabolism. Furthermore, the LAB strain and MLF process can contribute significantly to the wine’s style.

Monitoring MLF

As many wineries approach colder daily temperatures, it’s important to monitor environmental and storage conditions of those wines that are undergoing MLF until the process has completed. Otherwise, MLF can become stuck or “pause” until the temperature of the wine warms again or conditions become otherwise favorable for MLF to proceed (e.g., sulfur dioxide concentrations decrease).

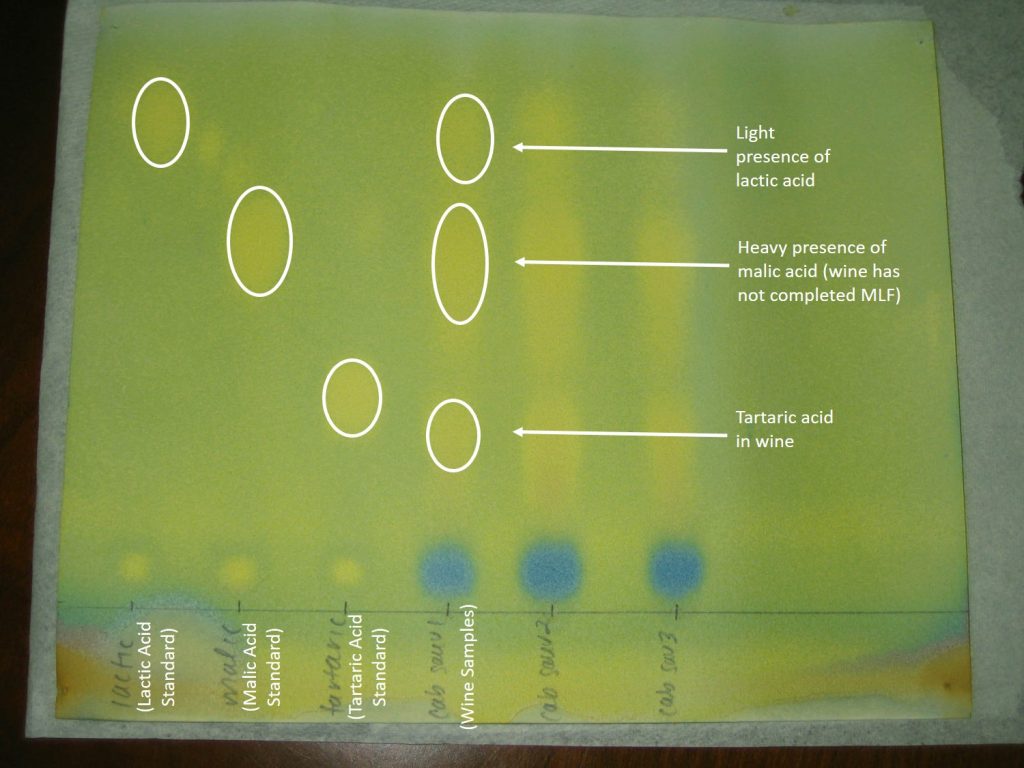

I recommend monitoring the MLF weekly. Many winemakers monitor MLF using paper chromatography, which is a suitable way to monitor the MLF process. The webinar, “The Dot Races,” and its downloadable notes addresses practical MLF monitoring techniques and how to properly run a paper chromatogram.

If the winemaker is not monitoring MLF, a stuck MLF may lead the winemaker to believe MLF has completed when in fact residual malic acid remains. Luckily, “The Dot Races” also discusses the limitations of paper chromatography for monitoring MLF as well as disadvantages for not monitoring MLF at all. In many cases, failing to monitor MLF can lead to wine spoilage or post-bottling MLFs.

What to do with stuck MLFs

Nonetheless, there are times when MLF becomes stuck before it has completed to dryness (defined in practice at <0.3 g/L malic acid). Re-starting a stuck MLF can be a tricky and time-consuming process. Unlike primary fermentation, constantly adding commercial LAB can actually be more problematic than helpful.

If the wine is not “dry” for malic acid, but the MLF is not progressing, then a winemaker should work on re-starting the MLF to complete it sooner rather than later. Without adequate sulfur dioxide levels to preserve the wine, waiting until the warmer Spring or Summer months for the wine to warm up may not be advantageous for the wine’s quality. Often, this waiting period leads to wine spoilage with rising levels of volatile acidity due to acetic acid bacteria activity. (This also raises the point that monitoring volatile acidity is a helpful indicator that things are going smoothly during MLF. If the winemaker knows the pre-MLF volatile acidity, then a dramatic increase in the volatile acidity during MLF can indicate a problem with acetic acid bacteria spoilage.)

So what can a winemaker do when the MLF is stuck? Or, presumably stuck?

First, measure the malic acid concentration. Has the MLF reached dryness?

If the answer is no, winemakers may have to try to re-start the MLF. The webinar and its downloadable notes, “Re-Starting a Stuck Malolactic Fermentation” reviews key concepts associated with stuck MLFs. It also explains a 5-step process for trying to re-start a stuck MLF. Furthermore, the Production Guide: Re-Starting a Stuck Malolactic Fermentation provides five areas for the winemaker to consider and detailed parameters for adjustment if a MLF gets stuck.

Finding incomplete MLFs are one of the key areas I see wines begin to spoil. Don’t let this happen to your wines! With a little persistence that we use during harvest and primary fermentation, winemakers can better wine quality simply by staying on top of the MLF and monitoring its progression.

Don’t forget!

If you’re a regular reader of the DG Winemaking Blog, first – thank you!

Now, we’re offering access to many of these materials through a DGW Insider membership.

Or, if you’d like to start joining our twice monthly Winemaking Q&A sessions with Denise Gardner and additional DGW Community members, while also gaining access to the website materials, the DGW Elite membership offers these exclusive services and more!

Read more about DGW Insider and DGW Elite memberships on the DG Winemaking Services page.

References

Iland, P., P. Grbin, M. Grinbergs, L. Schmidtke, and A. Soden. 2007. Microbiological Analysis of Grapes and Wine: Techniques and Concepts. Patrick Iland Wine Promotions Pty. Ltd. Australia. ISBN: 978-0-9581605-3-7

Krieger, S. 2005. The history of malolactic bacteria in wine. In Malolactic Fermentation in Wine: Understanding the Science and the Practice. Lallemand, Inc. Montreal, Canada. ISBN: 0-9739147-0-X