Formula Wine Production, Regulatory Challenges, and Yeast Selection

As many of you know, I regularly attend the Eastern Winery Exposition (EWE) Conference. The conference gives me a chance to see what’s new among tradeshow vendors and catch up with many familiar faces.

You’ll usually find me at the American Society of Enology and Viticulture – Eastern Section (ASEV-ES) auction, helping to raise money for viticulture and enology student scholarships. This year, I appreciated Chris Gerling’s, Extension Enologist at Cornell University, perspective on how the ASEV – Eastern Section students are likely studying in a home state of most of the people attending the conference.

You may know I’m a past ASEV-ES scholarship recipient and thus, I’ve experienced the benefit of these scholarships first hand. The support is highly appreciated by recipient students.

However, I digress. This year, there were a few things that caught my interest at the EWE Conference. Here are a few thoughts on things that caught my attention from presentations I participated in as a panel presenter.

Formula Wines are Everywhere

I was fortunate to speak alongside Alcohol Beverage and Food Attorney, Lindsey A. Zahn.

I focused my presentation on making formulaic wines with intention to drive quality and consistency. While providing some overarching production tips to winemakers in the audience, I also highlighted some large market changes that have changed the types of wines that I see on grocery and retail shelves. These include:

- A decrease in premium wine sales.

- Availability and use of cans as alternative packages for wines, which first became trendy around 2017, and has since become more accessible to various wine regions across the U.S., as shown here.

- A greater interest and increase of sales for ready-to-drink cocktails, which the wine industry has previously honed into with the production of various formula wines.

The unfortunate part of this wave for wineries is that breweries, hard cideries, and distilleries are all participating in this market. You can see some headline examples here (Dogfish Head), here (Naughty Tea Wine), and here (Boulevard Brewing). Even Keurig, a non-alcoholic beverage company, is now entering the ready-to-drink cocktail market.

To emphasize this point, Lindsey commented to me how formula submissions for something like hard seltzer water vary so dramatically from producer-to-producer, but also based on the type of producer (brewery, winery, and distillery) that manufactured the product.

Even if your winery sells most of its wines out of the tasting room, I would argue that being aware of the market is essential. Your competition may be the local wine retail store or various brew pubs that line the local Main Street.

Producing Quality Formula Wines

The increased concentration of these wines/beers/spirits ultimately leads to a quality race to compete with other producers. There are definitely beverages on the market that look fantastic and have an amazing taste. And then there are those beverages that look fantastic and taste horrible.

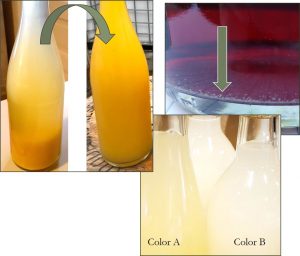

At EWE, I tried to stress that creativity and planning is key to competing in this market. Planning sounds like an unnecessary step, but I find many winemakers stumble when they give themselves a one- to two-week timeline to finish stabilizing, formulate, and bottle a formula wine. Typically, these winemakers deal with post-bottling instabilities more prevalently associated with formula wines including precipitate formations, discoloration, and flavor loss.

I encourage winemakers to understand the base wine chemistry associated with their formula wines. Like with sparkling, ingredient additions and processing steps impact how a formula wine will “behave” post-bottling. This becomes more complex with ingredient additions that are a bit outside the norm for traditional wines.

If you’re a DG Winemaking client, you can get some inside tips on formula wine ingredients in the article “Formulating Untraditional Wines and Wine Products” as well as a pre-bottling checklist for formula wines in this DGW Production Guide.

There’s also some free info in past a blog post, “Crafting Formula Wines with Intention.”

Do you want to learn more about formula wines? Take our 2 question poll by clicking on the button, below.

Submitting Formula Approvals to the TTB

Lindsey focused on the TTB formula wine submission/approval process. The definition for a formula wine is found the 27 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 24.10:

Formula wine. Special natural wine, agricultural wine, and other than standard wine (except for distilling material and vinegar stock) produced on bonded wine premises under an approved formula.

This is a rather vague definition and does put the onus back on the producer/winery to understand the CFR for wine. The TTB requests formula submissions to ensure that the wine is in the proper tax category, create appropriate label terminology reflective of current wine regulation, ensure ingredients are safe (GRAS), and that ingredients added are used within proper allowable limits for alcoholic beverages.

It’s important to understand that when and how you add specific ingredients can determine whether or not a wine is required for formula submission and TTB approval. When a formula is required, Lindsey emphasized that formula submission is kept confidential, and encouraged wineries to accurately disclose their formula recipe that is reflective of how the wine is produced in the winery.

Wild vs. Commercial Yeast Fermentations

I was also very fortunate to speak alongside James Callahan, winemaker at Rune Wines in Arizona (seriously… check out this winery!) and Michael Reidy, winemaker at Hazlitt 1852 Vineyards in New York. I thought both of these winemakers provided great insight into both the benefits and challenges associated with wild or commercial yeast fermentations.

One of the key themes that kept coming up was the fact that a winemaker can make amazing wine using wild yeast fermentations or they can make amazing wine from commercial yeast fermentations.

However, a winemaker can also make pretty terrible wine using wild yeast fermentations or they can make pretty terrible wine from commercial yeast fermentations.

I’d have to say this is very true. I’ve seen (and tasted) both extremes capitalizing on both fermentation strategies.

The key thing to remember is that when winemakers select wild yeast fermentations, the fermentation is almost always finished by a commercial yeast strain. The yeast is fairly ubiquitous and several studies have shown that once a commercial yeast strain is used in the winery, it pretty much hangs out in the winery for all time.

A few years ago, I was at a talk given by a UC Davis professor who showed us a map of the new winery that was built for the current Viticulture and Enology Department. They managed to show various populations of yeast and bacteria within the winery before a single grape hit the production floor.

In the early 2010s, about six wineries from Oregon evaluated the microflora in their grapes upon harvest vs. the microflora during primary fermentation. Many well-known Pinot Noir producers in Oregon emphasize the use of wild yeast fermentations. But what they found: the winery strains dominated the fermentations. If you’re lucky enough to log into Wine Business Monthly, you can see the article, here.

While these situations are well-documented, it really gives light to why the winery is so influential to the winemaker processes. What a winemaker does matters. This isn’t to say that wild yeast fermentations don’t contribute to complexity. They can. However, using commercial yeast strains can also create a complex wine. Some of the complexity comes from measures beyond primary fermentation yeast selection.

And that’s why understanding enology and the influence of various winemaking practices or procedures is so important.