Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

The second season of HBO mini-series, “The Gilded Age” recently dropped, highlighting the opulence of New York City during the time of rapid industrial growth of the Gilded Era (roughly 1875 – 1900) through the lens’ of two wealthy women. While the series is caught between the “Old New York” elite and industrious “New Money” that comes into New York City, I couldn’t help but notice the regular footage featuring wine and food. It struck me that this time in American history may contain interesting insight into American wine culture today. I was completely surprised by what I found!

A wine glass should be ‘held by the stem, not by the bowl,’ and one must ‘never drink a glassful at once, nor drain the last drop.’”

– Quote from What Would Mrs. Astor Do? by Cecelia Tichi

Historical Backdrop of the Gilded Era

The Gilded Era is often noted as a short period of time following the close of the U.S. Civil War (1861 – 1865) and following the national reconstruction. While the Southern U.S. remained devastated by the Civil War, New York City became the poster child associated with the opulent Gilded elite (Phillips, 2001). The Gilded Era is marked by its strong juxtapositions during this period of time, especially with regards to the rise of industrial and investment moguls while many Americans, immigrants, and minorities were living in poverty. This is the time of the Vanderbilts, the Carnegies, and the Rockefellers among the Morgans and many other moguls of this time.

Agriculturally, the country was changing. The integration of the railroad system across the U.S. made shipments easier for distribution. Regional goods were becoming a thing of the past. Refrigeration was not yet invented and, thus, the ice industry dominated shipping perishable produce on rail car.

The wine industry was also impacted during this time. The scientist, Louis Pasteur, had just recently discovered that wine was a result of a biological, microbial transformation of sugar to alcohol in the 1850s-1860s (Phillips, 2001). There was ongoing interest in vineyard establishment in the Eastern U.S. However, many vineyards suffered from grapevine disease due to the climate. And, as it would be recognized later, due to the presence of phylloxera. Ultimately, growing challenges led to a rise in Concord and Catawba vineyards, which many used for wine production (Phillips, 2001; Pinney, 2007).

Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

At the same time, the Western U.S. wine industry was just getting established. The Western wine industry was not yet the powerhouse we know today. By the Gilded Era, several vineyards and winery operations existed. Mission and Zinfandel were the primary red varieties grown while Chasselas was the primary white variety grown (Phillips, 2001). Chasselas is not easily found in the U.S. today, but is the primary white grape used to make Swiss wine (Robinson, Harding, and Vouillamoz, 2012). Of course, Zinfandel is still widely produced in the U.S., but the Mission wine grape variety, a Spanish variety, is primarily used for American Sherry or Port-style wines (Robinson, Harding, and Vouillamoz, 2012). Unfortunately, to the elite in New York City, these wines produced in the U.S. were not up to par for presentation and enjoyment in the mansions of Fifth Avenue.

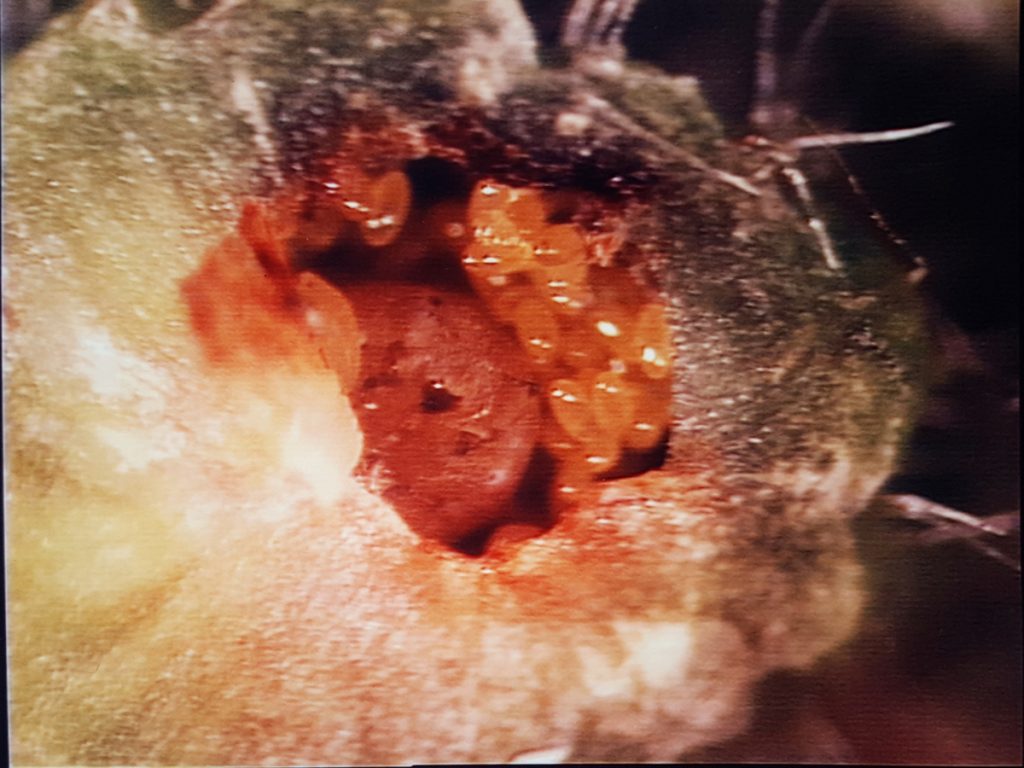

Internationally, the phylloxera epidemic was growing in Europe. Phylloxera, an extremely small root insect, was transferred to Europe during the 1850s – 1860s when vines from America were shipped to Europe. Native to the U.S., the insect was not previously present in Europe, but actively feeds upon the roots of Vitis vinifera (European) wine grape varieties that are cultivated acres of vineyards throughout Europe. (V. vinifera varieties include many of the wine grape varieties we often associate with wine, and include varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Grigio, Chardonnay, and Riesling, just to name a few.) The introduction and establishment of phylloxera led to the rapid decline of European vines, and thus, European wine. By the 1870s, there was an aggressive international movement to “cure” the phylloxera problem (Phillips, 2001). It wasn’t until 1881, in which grafting American vine rootstocks onto European vines was proposed (Phillips, 2001). This was ultimately the solution that saved the wine industry we know today.

Light Microscope Image by: Denise M. Gardner

Light Microscope Image by: Denise M. Gardner

Finally, the temperance movement was gaining momentum in the U.S. during the Gilded Era. While national Prohibition did not start until 1920 (ending in 1933), the start of temperance began in the latter half of the 1800s. While many in the wine industry hoped that wine would be omitted from a temperance movement, as we all know, a complete national Prohibition would eventually become a touchstone of American history.

Wines of the Rich during the Gilded Era

Again, while the Gilded Era was filled with a lot of juxtapositions, wine culture was highly emphasized by those with money in New York City. If you ever thought that there were way too many rules associated with wine enjoyment, one need not look too much further than the elite society of American Gilded Era to capture an essence of where these rules were put to extreme use.

French culture and fashion were extremely revered, to excess, during the Gilded Era (Tichi, 2018). Thus, it should come at no surprise that in addition to obsessions with French cuisine, French wines were valued and collected by the wealthy (Tichi, 2018). Ironically, phylloxera was devastating French vineyards while the New York City socialites were collecting French wines in excess!

Amongst “The Four Hundred,” the name given to the group Mrs. Astor considered a part of New York elite society, different times of day not only required different forms of dress for both men and women, but different types of wines, too. The time of day and type of occasion dictated the appropriate etiquette for which wines would be served (Tichi, 2018). You can sometimes capture this throughout Season 1 of “The Gilded Age,” especially when Agnes makes mention of a “lunch wine,” which was likely a red Claret of lower status (lower price).

The most extreme examples of wine selection were during formal dinners or balls hosted by the families that inhabited the Fifth Avenue mansions in New York City. The primary wines of this era included Champagne (French wine), Sherry (Spanish wine), Madeira (Portuguese wine), and [vintage] Claret (French wine) (Tichi, 2018). At this time in history, “Claret” was a catch-all term for vintage Bordeaux red wines. Additional wines that could be found at formal dinners included: Moët & Chandon Nonvintage White Star Champagne, Burgundy Pinot Noir, Rheingau Riesling, Tokay, and various Bordeaux wines that ranged from general table wines to respected and rare château wines (Tichi, 2018). Given that the 1855 Classification system was defined before the Gilded Era, I would suspect that some of the French wine collections contained many of these châteaux that have become recognizable by name: Château Lafite Rothschild (Pauillac), Château Latour (Pauillac), Château Margeaux (Margeaux), Château Haut-Brion (Pessac, Graves), Château Mouton-Rothschild (Pauillac), and many additional estates. In fact, one wine list within Tichi’s book on the Gilded Era made mention to the purchase of Château Mouton wine (Tichi, 2018). To find the full classification list, you can refer to this list on Wine Spectator.

One popular Champagne at the time was Moët & Chandon Nonvintage White Star, which was discontinued in 2009.1 This Champagne was specifically produced for the U.S. market with a higher sweetness level compared to their house Impérial Brut. 1 Using the current sweetness scale, it is likely this wine would have been classified as “Extra Dry” given the sweetness level.

What is noticeably absent from the New York City lifestyle are American produced wines. Again, there was little or no interest in the Concord wines gaining momentum in the Eastern U.S. After the Civil War, the wine industry of California was just getting established (Pinney, 2007). The California brands that existed during the Gilded Era, and would later survive Prohibition, include Gundlach Bundschu, Charles Krug, Almaden Vineyards, Mirassou Winery, Beringer Vineyards, Inglenook, Simi Winery, Wente Vineyards, Concannon Vineyard, Geyser Peak Winery, and Chateau Montelena (Pinney, 2007). Many of these brands would develop national reclaim in the 20th century.

Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Drink Like the Gilded Age Elite

Ironically, many of us can taste wines that Mrs. Astor, Agnes Van Rhijn, or Bertha Russel enjoyed in their dining rooms or drawing rooms. Perhaps we cannot taste the same vintages, but we can certainly taste many of the brands that were popular at this time.

Nothing could be more splendid!

Below, I’ve listed some wine selections that I found reference to in the book, “What Would Mrs. Astor Do” by Cecelia Tichi (2018). For those wines that are the same brand and style today, I’ve listed them. For those that no longer exist or were less specific in my reading, I’ve improvised suggestions with wines that could have been a part of this time. The wines are listed in order of style and sweetness (least sweet to sweetest), which exception to Madeira. I’ve provided 4 different Madeira wines, listing the driest (least sweet) first, and sweetest, last. Note, however, that the order of all of the wines, below, does not reflect the absolute order in which the wines would have been served during Gilded Era formal dinners.

Irroy Extra Brut

At the time of the Gilded Era, Irroy Champagne was a member of the Syndicat des Grandes Marques2 (Union of Major Brands) to protect the quality of Champagne sparkling wines. Remember that the Gilded elite were obsessed with French wines, and thus, Champagne was high on the list for preferences. The Irroy Champagne was founded in 1820, and thus, readily available during the Gilded Age. This grower Champagne fell under Tattinger Champagne ownership in 1955.2 Depending on where you purchase wine, one can find the “Extra Brut” Champagne style, a drier style than “Brut,” which was more common during the Gilded Era.

Moët & Chandon Impérial Brut

The Moët & Chandon Impérial Brut Champagne, created in 1869, was a staple of the Gilded Era (Tichi, 2018). The Champagne blend typically consists of a mixture of all 3 Champagne wine grape varieties: 30 – 40% Pinot Noir, 30 – 40% Pinot Meunier, and 20 – 30% Chardonnay. This is a fairly popular Champagne wine brand and label today.

Burgundy Wine

I have to admit that navigating Burgundian Pinot Noir wine is difficult even for me. Burgundian wines are labeled by village name or with additional terms “Premier Cru” or “Grand Cru.” This is to specify the quality lineage with the village name being of lowest quality, “Grand Cru” as the highest, and “Premier Cru” in the middle (WSET, 2012). Typically, one will find “Premier Cru” Burgundy wines are more expensive than village Burgundy wines, and the “Grand Cru” wines are the most expensive of all. What’s tricky, in my opinion, about Burgundy is finding the regions within Burgundy that you prefer taste-wise. Recently, I had some Pinot Noirs from Gevrey-Chambertin and enjoyed them. Thus, I’m linking a Bouchard Pere and Fills 2018 Gevrey-Chambertin here even though it doesn’t fall into the “Premier Cru” or “Grand Cru” category that would likely be sought after by the wealthy Gilded Age moguls. You’ll see it’s still pricey!

Médoc Cru Bourgeois (An Alternative to “Bordeaux Supérieur”)

The Médoc region is a part of the Left Bank of the Bordeaux wine region. The “Supérieur” terminology on a Bordeaux wine label is usually indicative of closer vine plantings and more rigorous fruit/wine chemistries for its classification. I would not say the “Supérieur” term on a Bordeaux wine label indicates that the wine tastes better.

Nonetheless, the Médoc region was popular during the Gilded Era. The Cabernet Sauvignon wine grape variety tends to dominate blends for Médoc wines. Although the 1855 Classification of Bordeaux included a few Médoc producers, there were many that were omitted. Today, producers outside of the 1855 Classification can submit a vintage wine for “Cru Bourgeois” status, but this award is only granted for each individual vintage, not the actual brand or château (WSET, 2012). Given how the Gilded Era rich favored such prestige, I would imagine finding a Cru Bourgeois Médoc wine would be a good fit for a tasting! I found one within a retailer I can purchase from, Château Haut Barrail 2018 Cru Bourgeois, which was recommended for consumption after 2023. However, other châteaux exist with this designation and would be an appropriate alternative. Or, you could opt for a fifth-growth Bordeaux from the 1855 Classification: Château Belgrave 2019 Haut-Médoc, which is rather affordable.

Domaine Chandon Reserve Club Cuvée

While Moët & Chandon’s Nonvintage White Star was discontinued in 2009,1 several tasting and distribution sites have listed it as an “Extra Dry” Champagne, confirming the elevated sweetness that is assumed to appeal to the American market during its introduction. Therefore, I’d recommend Domaine Chandon’s Reserve Club Cuvée, the sister American winery to Moët & Chandon3 (both currently owned by the luxury goods company, LVMH, at the date of this release). The Reserve Club Cuvée is considered “Extra Dry” in the sweetness level (slightly sweeter than “Brut” sparkling wines), and thus, can act as an alternative to capture the White Star wine style of the Gilded Age.

Sherry

Unlike other fortified wines, Sherry can be both dry or sweet. Given Sherry’s history, I’m going to guess that Amontillado or Olorosos Sherry was sought after by the wealthy during the Gilded Age. These Sherries are aged up to a combined 30 years and have an alcohol concentration of about 22% (WSET, 2012). Both Amontillado or Oloroso are “dry” (not sweet). Lustau Solera Los Arcos Dry Amontillado Sherry or Lustau Don Nuno Dry Oloroso Sherry are affordable, though mid-range in terms of quality for dry Sherries. If you would prefer a sweeter alternative, I would try a PX Sherry, which could have been used in some percentage of an Oloroso Sherry (WSET, 2012). Valdespino Pedro Ximenez (PX) El Candado has relatively good ratings for the price.

Schloss Johannisberg Riesling (Rheingau, Germany)

The Rheingau region of Germany is known for its historical Riesling vineyards, with distinct differentiation in flavor compared to the popular Mosel region in Germany. Within the Rheingau is the tiny sub-region, Johannisberg.4 One of America’s Founding Fathers, Thomas Jefferson, favored Schloss Johannisberg wine.5 Therefore, while I’m not certain which Johannisberg Riesling was favored during the Gilded Era, for this tasting, I selected Schloss Johannisberg since it has American prestige as I’m sure the wealthy Gilded moguls would appreciate its heritage.

Madeira

While Madeira was often reserved for the men during the Gilded Age (Tichi, 2018), I have to admit that this is one of my favorite wine styles. I’ve previously discussed Madeira wine, as it played an important role in U.S. Independence from Britain. During the time of the Gilded Era, it’s likely the noble varieties were still produced heavily: Sercial, Verdelho, Bual (Boal), and Malmsey (Malvasia). Each have a designated sweetness level: Sercial was the driest and Malmsey the sweetest. This is still true today. Madeira wine is high in alcohol, as it is a fortified wine like Sherry. However, what made Madeira unique was the aging process and its impact on wine flavor: held in ships that traveled across the Atlantic, the wines aged in a unique way causing the wine flavors to caramelize. Today, production alternatives to “sea aging” are used. However, finding noble variety Madeira is still a real treat. I’ve primarily been able to find the Blandy’s Brand, and commonly find both 5-Year and 10-Year Old Madeira’s though older wines exist: Sercial, Verdelho, Bual, Malmsey.

Pellegrino (Mineral Water)

No table of the Gilded Era was complete without sparkling mineral water. The popular brand at the time was Apollinaris (Tichi, 2018), which is a mineral water produced in Germany. Today, Apollinaris mineral water may be difficult to find, and thus, you may have to settle for S. Pellegrino.

If You Want to Learn More…

This post mentioned facts from the following resources:

A Short History of Wine by Rod Phillips. 2001.

A History of Wine in America, Vol. 1: From the Beginnings to Prohibition by Thomas Pinney. 2007.

What Would Mrs. Astor Do? by Cecelia Tichi. 2018.

Wines and Spirits: Understanding Style and Quality, Produced by the Wine & Spirit Education Trust (WSET). 2012.

Wine Grapes by Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, and José Vouillamoz. 2012.

In addition to information from the following websites:

1Wine Auctioneer. Moet & Chadon White Star NV Champagne. Available at: https://wineauctioneer.com/lot/8861/moet-chandon-white-star-nv-champagne#:~:text=%22White%20Star%22%20was%20%2D%20until,the%20regular%20%22Brut%22%20style

2Champagne Irroy. Available at: https://www.champagneone.co.uk/irroy/

3The Napa Wine Project. Domaine Chandon. Available at: https://www.napawineproject.com/domaine-chandon/#:~:text=Domaine%20Chandon%20was%20founded%20in,Bertrand%20Mure%20and%20another%20executive%2C

4Wine-Searcher. Johannisberg Wine. Available at: https://www.wine-searcher.com/regions-johannisberg

5Raper, J. “New Bio Reveals Jefferson’s Passion for Wine and Travel.” August, 1996. The Virginian-Pilot. Available at: https://scholar.lib.vt.edu/VA-news/VA-Pilot/issues/1996/vp960804/08010041.htm

Photo by: Denise M. Gardner