Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Said: Sham-bore-sin

In a world where farmers are experiencing changes in weather patterns that affect grape ripening potential, wine grape hybrid varieties may play a greater part in the future of our wine industry. But what are hybrid wine grape varieties? What kind of wines do they make?

As someone who has regularly pointed out that there are many Hidden Wine Gems across the U.S., I think it’s time to also dive into some of these lesser-known wine grape varieties.

At best, these wine grape varieties offer winemaking options for both grape growers and vintners. At worst, many of the wines produced from such varieties are downplayed by wine industry experts and sommeliers. What is often forgotten is that most wine lovers are not looking for a refined Bordeaux wine, but something enjoyable, easy-to-drink, and of good quality.

When varieties have such great potential, why do we spend so little time focusing on the wines they make and where you can find them?

The answer, and more, in today’s Hybrid Hy-Light!

Chambourcin’s History

Chambourcin was bred by French biochemist, Joannes Seyve, in the 1940’s and made available for commercial use in 1963 (Robinson, Harding, and Vouillamoz, 2012). It is named after a place where Seyve owned an experimental vineyard in Isère, France (Robinson, Harding, and Vouillamoz, 2012).

But knowing that some French guy bred the Chambourcin grape variety provides little context as to why this variety was created or why this scientist even cared about breeding wine grape varieties to begin with!

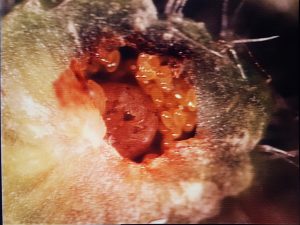

By the mid-1800’s phylloxera, a small insect native to North America that infects grapevine roots and, sometimes, grapevine leaves, had been devastating the European vineyards. Phylloxera was transported from the America’s to Europe through plant distribution. Today, we know that North American grapevine species are tolerant of phylloxera, meaning that grape roots can support phylloxera populations without the vine dying. However, European wine grape varieties (like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, etc.) are fully susceptible to phylloxera, and over time, the vine will slowly succumb to the insect and die.

Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

The phylloxera devastation of Europe’s most treasured vineyards was the match that lit the fire on saving the wine industry. At this time, many solutions were being tested to determine what would ultimately save the wine grape varieties that the world had come to rely on and love.

Ultimately, the solution ended up being a procedure called grafting, in which native American-based grape species were used as roots (called rootstocks) while the top part of the vine of European grape species were cut and connected to the rootstock. This top portion is called a scion. Grafting is used all over the plant industry to gain benefits from the root portion of a plant while also gathering benefits from the top portion of another plant. The cut, or the graft, is made in a specific pattern on both parts of the plant. The two parts are placed together, much like piecing a 3D puzzle together, and then the graft is wrapped in a bandage. Over time the graft, in fact, becomes one plant, as the vascular systems of the two different plants merge together allowing for water and nutrient transfer through both the rootstock and scion. Again, grafting is still wildly used in the grape industry to this day.

Grafting wine grapes was not accepted with open arms. There was a lot of fear that undesirable American grape characteristics, specifically “foxy” flavors, would get into the beloved European grapes and, hence, change the wine the wines tasted (for the worse). Obviously, this didn’t happen. As science has progressed over the centuries, we now know that varietal flavor development occurs in the berries and is not something that is transferred through the vascular systems.

However, that fear was still a very large part of the solutions behind grape phylloxera and the fixes for it in the 1800s. Hybridization, the breeding of American and European species together to create a third, unique species, was viewed as a possible solution in the race to save the wine industry during the devastating phylloxera years. Initial grape hybrids were likely 50:50; 50% American and 50% French (for obvious reasons), but over time, many scientists, especially in France, started breeding hybrids with other hybrids or hybrids with other American or French varieties. It is likely that Seyve was a part of this effort. This mixing creates complex lineages of what a hybrid’s parentage looks like! That diversity ultimately led to some of the French-American hybrids that we know today: Chambourcin and Seyval, for example.

“The real turning point came in the course of World War II. So far as France is concerned, this provided the acid test, for labor was scarce and copper and sulfur practically unobtainable. The vinifera vineyards in the mass production areas were riddled with disease. The vineyards of hybrids came through, on the whole, very well.” – Philip Wagner, 1955

The term “French-American” was used when varieties like Chambourcin were imported into the U.S. to evaluate their potential for growth and success in the Eastern U.S. (Pinney, 2005). In particular, Philip Wagner, one of the pioneers in rejuvenating the Eastern wine industry after WWII, coined these varieties as “French-American hybrids” to differentiate them from some of the earlier hybrids that had initially been bred to take on phylloxera (Pinney, 2005). One of the benefits of Chambourcin was that it displayed a fair amount of cold hardiness, meaning it was able to withstand the harsh winters associated with several Eastern U.S. states, and grow grapes through full ripening potential during the growing seasons (Pinney; Wagner 1955).

“The end of Prohibition, however, did stimulate an interest in grapes suitable for wine-making that would grow in our eastern districts. This demand came to some extent from the established eastern wineries, but also from persons who, during Prohibition, had been accustomed to make wine of California varieties shipped East.” – Philip Wagner, 1955

From the initial settlements made in the Eastern U.S., the practice of growing grapes for wine was a long series of failures. In large part, this was due to the natural habitation of phylloxera in North America. The varieties brought into new colonies were grape varieties from Europe susceptible to phylloxera. While most of the East had resorted to making wine from native varieties, or primarily native varieties, those varieties were often viewed in an inferior light (Read: “The Unmentionables” for more information). With the importation of the “new” French-American hybrids that were bred in France, and Wagner’s work with them in Maryland (Pinney, 2005), not only could wine grapes with superior wine quality characteristics be grown, but they provided a new life to the Eastern and Mid-Western industries after Prohibition. In time, the use of grafting would also provide opportunity for many of the European varieties to grow successfully in these regions, as well.

Photo by: Bartlett Pair Photography

What do Chambourcin wines taste like?

The benefit with Chambourcin is that it can be used for many different styles of wine:

- Dry, Red Wines, including the 2 Taste Categories:

- Rosé Wines, in both categories:

- Dry Rosés

- Sweet Rosés

- Sweet, Red Wines

On rare occasions, it is possible to find Chambourcin used in Port-style, high-alcohol (fortified) wines, dessert wines including ice wine, and even sparkling wines.

However, this benefit of versatility also makes Chambourcin a challenge for many wineries to sell as it is impossible for Wine Lovers like us to know what to expect from a bottle labeled “Chambourcin” without a little more detail provided by the producing winery.

Chambourcin was often hailed as the red hybrid grape variety that would replace many Vitis vinifera (European species like Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot) wine grape varieties in regions that found growing V. vinifera grapes difficult. However, after several decades of trial and error, and a lot of winemakers trying to fit Chambourcin into a Cabernet-hole, I think many vintners have concluded that Chambourcin, like many red hybrid grape varieties, are their own beasts.

As a dry red wine, Chambourcin can be quite approachable. First, when the acid structure is ideal, it provides a deep, ruby-red to purplish color that many Wine Lovers truly love. Chambourcin lacks significant astringency, often rendering the wine “juicy” and “soft.” It’s also relatively neutral, carrying generic red wine, red fruit, and red cherry flavors. The complexity in Chambourcin’s flavor profile rests in the earthy-flavor component, which some Wine Lovers may find off-putting. With oak aging (Taste Category: Oaky Reds), Chambourcin red wines can also carry a multitude of oaky flavors in addition to the fruit flavors, which include, but are not limited to: spice (nutmeg, cinnamon), toasted oak, marshmallow, vanilla, smokiness, roasted coffee, and dark cocoa.

The lack of astringency, which contributes to a lighter mouthfeel, may be one of the key sensory characteristics that differentiates Chambourcin wines from V. vinifera wines. Most Chambourcin wines that you taste will ultimately have a lower body, or feel thinner, than Cabernets or Red Blends produced from the West Coast. Nonetheless, even with this attribute, I have had several lovely Chambourcin wines that were aged for 10+ years after bottling. Thus, this sensory “deficit” in Chambourcin red wines should not inhibit collectors from cellaring Chambourcin wines of good quality.

Sweet Chambourcins typically lack any oak-related flavors, and, instead focus on the fruit flavors within the red wine. Tasting tip: Make sure to chill wines that are sweet, even if they are red! The cooling provides a more enjoyable tasting experience.

In contrast, the Rosés of Chambourcin are completely different! Chambourcin Rosés, especially those that are 100% Chambourcin, will range in color from a pale salmon to a dark, deep fuchsia red. Remember that color plays zero role in the wine’s quality (well, except if the wine is “brown”), but it does play a strong role in biasing your expectation of what the wine should taste like! A lot of this variation in color is based on when the grapes were picked, the amount of skin contact the grapes had during rosé production, and the acid profile of the wine. Because Chambourcin often retains it’s acidity, the rosé wines tend to be vibrantly refreshing, and are relatively “juicy” and “soft” because there is a lack of astringency associated with this variety. The flavors are also delightful: citrus, fresh strawberry, sweet cream, and even bramble fruit.

Of course, sweetness intensity can vary among Chambourcin rosé wines.

Thus, it’s obvious to see here that there can be quite a strong variation in Chambourcin as a wine, even within a particular Taste Category or wine style.

Where can I find Chambourcin wines?

Chambourcin is one of the few red hybrid grape varieties that has some breadth in terms of where it is planted. Some of this is likely due to its early introduction to the grape growing industry.

Some states, listed in alphabetical order, that readily grow and produce Chambourcin wines include: Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. Chambourcin can also be found internationally in parts of Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, and Portugal (Robinson, Harding, and Vouillamoz, 2012).

Photo by: Bartlett Pair Photography

Why didn’t Chambourcin become the “next big wine thing?”

Ultimately, I don’t think the Chambourcin grape variety lived up to its wine potential as being a universal replacement for many V. vinifera varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Malbec, and many others. Even as early as 1955, Wagner was making documented notes of the prejudice against hybrid wine grapes, in general. I often simply say, “Chambourcin is just different,” as are many of the hybrid wine grape varieties. It has a much different mouthfeel and flavor profile compared to the more well-known, well-established V. vinifera wines that many of us know and love today.

But, I would argue, “different” does not equal “poor quality.” Like many wines in the market, there are many good quality, delicious examples of Chambourcin wine. However, there are also many poor quality, bad examples of Chambourcin wine. Thus, just with any wine exploration it will take just that – time to explore and find the Chambourcin wine producers that make high quality Chambourcin wines.

This post was written and supported by the following resources:

Pinney, T. 2005. A History of Wine in America, Volume 2: From Prohibition to the Present. ISBN: 978-0-520-25430-5

Robinson, J., J. Harding, and J. Vouillamoz. 2012. “Chambourcin” in Wine Grapes. ISBN: 978-0-06-220636-7.

Wagner, P.M. 1955. The French Hybrids. Am J Enol Vit. 6:10 – 17.